Reparative Fiscal Justice for Caribbean Climate Action

The intertwined challenges of climate and fiscal crises are devastating the ecologies and economies of countries around the world. This is felt most acutely in the Global South, which is swamped with debt, economically eroded by tax abuse, and forced to operate in a global financial system where rules are written by, and in favor of, the wealthy Global North. The Caribbean has a unique, heightened vulnerability to the crisis: as a result of past colonial plunder and modern economic exploitation, the region is among the most highly indebted in the world, and the climate is collapsing. Through discussions with movements and experts, as well as an analysis of the fiscal drain experienced by Caribbean governments through debt service and tax avoidance, this report underscores the urgent need for climate reparations—through both additional funding and structural economic reform—to address the intertwined economic and environmental crises gripping the region.

Recommendations:

- Cancel debt to enable investment in just climate action

- Force private creditors to participate in public debt restructuring

- Shift global tax rules to democratic governance by the UN

- Wealthy nations should provide reparative climate finance

- Reform international financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF to meet the challenges of the climate crisis

- Harmonize international climate action with ecological restoration

Learn about the report from author Fayola Jacobs

The report uses a mixed-methods approach to analyze the Caribbean’s dual crisis:

Quantitative Analysis

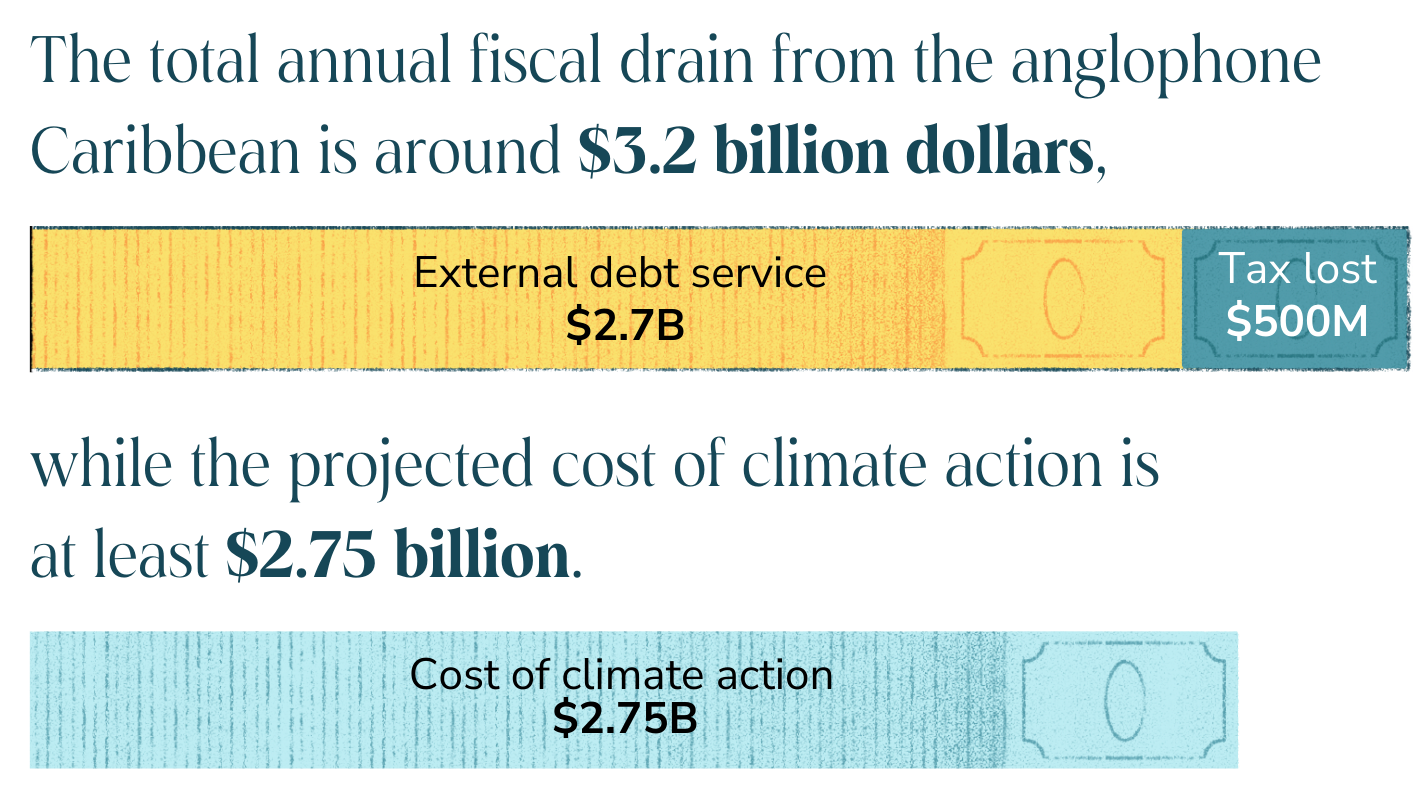

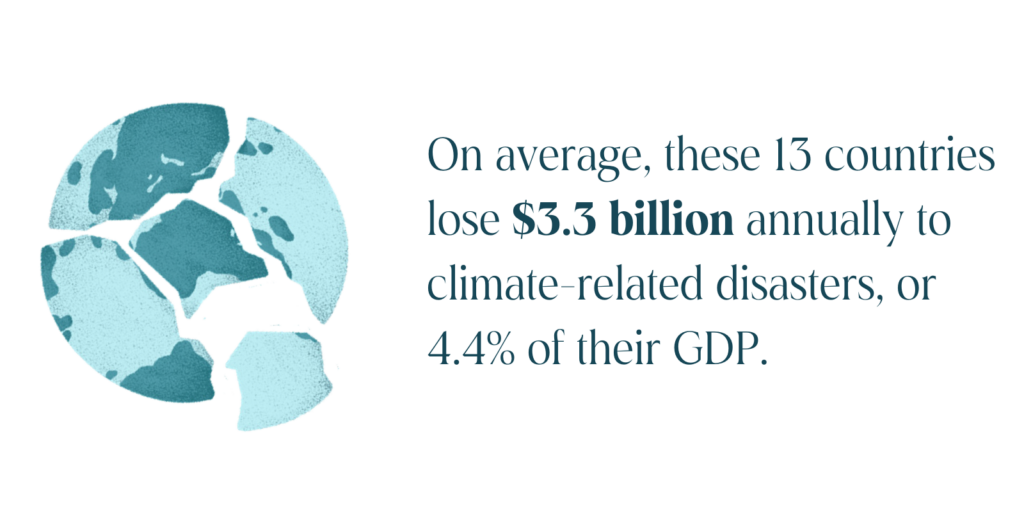

The report advances a quantitative assessment of the fiscal drain on Caribbean nations, demonstrating how unjust debt relations and an international tax system designed to benefit Northern corporations have siphoned resources away from the Global South – compounding the harms of colonization and slavery dating back hundreds of years. This drain severely limits the fiscal capacity of Caribbean governments to invest in sustainable development and other critical social and environmental priorities that could have myriad benefits. Instead, they are forced to devote scarce resources to climate adaptation and mitigation measures or recovery efforts after disasters strike—all to defend against a crisis they had a vanishingly small role in creating.

By juxtaposing these findings with the projected costs of climate action in the region, the report highlights the stark disparity between the financial resources available—both in terms of domestic funding and, critically, international financing—and the investments required to combat the climate crisis effectively.

Expert Interviews

The report couples this quantitative analysis with a series of structured interviews conducted with regionally recognized experts in Caribbean climate and debt issues. Each interview featured a set of ten questions focusing on climate justice, debt justice, and reparative worlds, the most salient of which was: “If you had $X [where X equaled the amount of money the interviewee’s focus country loses annually to debt service and tax avoidance] more in climate action funding per year, what would your investment priorities be?” These interviews guided many of the reparative visions of this report.

Reparative Frames

Rather than recommend merely greater aid or traditional development assistance, the report advocates for transformative and restorative measures that allow Caribbean communities to build more resilient and sustainable futures. Among these measures are debt cancellation, equitable distribution of scaled-up climate finance, and comprehensive reforms to the international tax system.

We emphasize that these are necessary, but not sufficient, conditions. For transformative investment to yield a just climate future in the Caribbean, domestic political and economic reforms will also be necessary. Investigations of these reforms, however, given their specificity to each country, is beyond the scope of this report.

Taking this reparative approach, the report makes the case for climate reparations as a necessary step towards rectifying historical injustices and addressing the current climate emergency. Climate reparations are not merely financial compensation but a moral imperative. Accounting for past harms, including the disproportionate economic and environmental burden heaped on Caribbean nations by wealthier polluting countries through colonialism and ongoing extraction is critical. But we also have to change systems of power so that these harms do not continue.

To this end, the report concludes with a series of policy pathways aimed at advancing climate justice and fiscal reparations in the Caribbean. Among the pathways we propose are reforms to global governance institutions like the IMF and World Bank, initiatives for debt cancellation and climate finance, and more inclusive and equitable approaches to climate action that center the needs and priorities of Caribbean nations and puts an end to the global financial architecture that extracts from them–opening their fiscal capacity to pursue a just transformation to a climate safer future.

Reparative approaches to climate action should be about both redressing past harms and forging conditions that make different kinds of futures possible. The Caribbean needs climate reparations that cancel debt, reform international taxation, and restructure the global economic system to both restore fiscal capacity and ensure that these precarious conditions will not be reproduced in the coming decades.