It’s time to usher in a new era of water management in California

Key Takeaways

California’s water infrastructure has long been insufficient to deliver clean, affordable, or even sufficient water to all Californians; climate change is making a bad situation worse.

California’s system of water provision is built on disturbing legacies of colonialist and racist exploitation and abandonment, and Black, Indigenous, and Communities of Color suffer the most from the state’s approach to allocating water.

The recent signing of SB 389 signals that there is a growing appetite for transformative change to the state’s archaic, unworkable water rights system; it represents a good first step toward transformative change the deliver for California.

Hundreds of dams dot California’s riverways. Thousands of miles of canals crisscross the state, bringing water from distant reservoirs to desert urban centers. As the climate changes, this infrastructure is failing us. Reservoirs go dry as droughts drag on. Water in canals evaporates into increasingly warm air. Dams and levees fail to contain massive floods; water spills out to destroy whole towns and livelihoods. Over 1 million Californians are already water insecure. Climate change will increase that number without investments and updates to California’s water infrastructure and management approach. To sustainably provide water for all residents, California water management needs a paradigm shift.

Water infrastructure and management systems manage geographic and seasonal variability of water supply. Historically, conveyance systems and dams were built to move water from wet areas to mines, settlements, and farms beyond rivers and their tributaries. Conversely, in places with “too much” water, other infrastructural projects like reservoirs and levees were built to divert and store flood water and minimize damage. However, in the past, the highs and lows of water availability were more predictable — but with climate change, the extremes are going beyond what our system was built to handle.

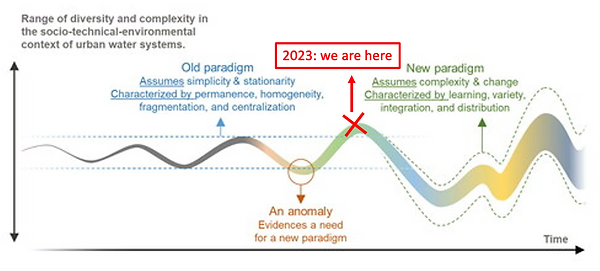

The new climate paradigm provides an urgent impetus for redesigning California’s water systems, just as efforts to manage geographic and seasonal variability in service of growing cities and farms was the driving force behind the current system. The figure below can be understood to show how infrastructure was built to handle a range of variability based on historical trends. But as climate variability no longer maps to historical patterns, the paradigm that governed the old management system breaks down, and a new way of thinking about water systems becomes imperative.

California’s hydrologic cycle is characterized by extreme highs and lows. This past year has been California’s tenth wettest year out of the past 128 years. From October 2022 to March 2023, California was hit by 31 intense storms caused by atmospheric rivers. In August 2023, a tropical storm hit the state for the first time in over 80 years. This comes on the tail of a prolonged drought, with three of the top five driest years in that 128-year period all occurring within the last decade. The extremes are happening closer together, creating “weather whiplash.” The recent rain has caused some to claim that the drought is over, but in reality, it is indicative of an ever more chaotic hydrologic cycle exacerbated by climate change.

Although surface water reservoirs have recovered after the drought, groundwater storage remains depleted from several decades of overuse, and recovery would require much more than one rainy season. Full surface water reservoirs also create flood risk when paired with above-normal to record level snowpacks in the Sierra Nevadas that will melt faster with each climate-change fueled heat wave. Indeed, many Central Valley communities already experienced flooding this year. In short, the current infrastructure does not have the capacity to handle the new climate extremes that are only going to intensify in the coming years.

Had green infrastructure, groundwater recharge projects, and stronger flood control measures already been in place before this historically wet year, the risk would not be so great. Instead, the record precipitation could have better restored groundwater aquifers that have suffered from the extended drought. Projects to implement such infrastructure before California’s next very wet or very dry year will go a long way in creating a more resilient system. However, infrastructural improvements alone will be insufficient to replenish the groundwater tables if there is no change to over pumping that diminishes aquifers.

The current system cannot handle this changing paradigm because of statutory limitations of the State Water Resources Control Board (or State Water Board). The State Water Board is the main regulatory agency for water in California. It has jurisdiction over surface water rights, sets quality standards, regulates pollutant sources, and monitors the state’s water. With the signing of SB389, the Board gained the authority to investigate water rights claimed before 1914. However, the State Water Board cannot effectively fulfill its mandate. It is not authorized to regulate or curtail water rights that were established before 1914, when its precursor agency was established. Because of this, water rights remain largely unchanged from their original distribution, and there is little that current management systems can do to regulate or reallocate water that is controlled by senior rights-holders.

Another major issue is that the current system is not built for fast action. The State Water Board cannot monitor diversions in real time; existing law requires only that surface water diverters report their diversions annually. When determining water shortage allocation decisions, state regulators are limited to using year-old data and cannot keep up with the constantly shifting water demand landscape. Historically, one of the major paths to change water systems is through litigation, which is often a years-long process ill-suited for the kind of rapid action needed to address climate extremes.

These issues with management in the current system did not happen by accident. California’s water infrastructure and water management systems have been twisted by racism and capitalism. The aforementioned caveats to the State Water Board’s authority have historical roots in settler violence and colonialism. The violent seizure of waterways and rights from Indigenous communities by white, male settlers, and the subsequent creation of management systems by those settlers created inequities that have persisted in the way that our water systems operate to this day.

Capitalistic priorities also warp the current system’s orientation towards water. Water is viewed as a commodity to be exploited; agricultural interests prioritize crop profitability, even if the most profitable crops are water-intensive and threaten ecosystems, communities with less power and resources, and future generations that would rely on them. These groups crafted and held positions of power to significantly shape future decisions. Managing water amidst the climate crisis will require a new paradigm with fundamentally different power dynamics.

Californians have limited time to upend systems built on a legacy of racism and capitalism, and replace them with water systems that are sustainable, resilient, and just. These systems must be designed with a set of guiding principles which can begin to undo some of the harms and challenges in the current water governance system. For example, water systems should be managed on the basis of watershed-specific democratic community governance to disentangle them from their racist roots. Also, decommodified water should be allocated to prioritize basic needs to address the current profit-motivated over-extraction of water. In actualizing these new systems, a high-road labor approach which values workers and pays them well can be one aspect of repairing historical wrongs. California must return land to tribes and prioritize environmental health so that these systems function naturally and sustainably for generations.