A Green New Deal for K-12 Public Schools

Transforming education

Public education in the United States has reached a critical point. Over the last 20 years, polling has shown that Americans are divided when it comes to their satisfaction with the K–12 public school system. There is a clear need for American schools to offer a broader portfolio of educational opportunities to students, to equip them for a full range of possible futures. Beyond questions of curricula, recent polling also shows that nearly two thirds of Americans are in favor of federal investment in public school buildings. And schools need the investment. The American Society of Civil Engineers has estimated that the country’s public schools require $380 billion just to meet standards of good repair—never mind climate resiliency and decarbonization.3 In June 2020, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that about 54 percent of all public school districts in the US need at least two major systems updated or replaced in most of their school facilities, and about 26 percent of all districts need at least six systems updated or replaced. The report called out the severe health and safety risks to students, educators, and community members from the “hazardous conditions” of public school facilities, noting the number of schools that had to close even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. A June 2021 NBC news story detailed the scope and scale of these problems, particularly in low-income school districts.

In addition to these calls for transforming the mission, priorities, and funding streams of public education, public school buildings and districts have long been a battleground in state and local politics. They are often where the long legacy of segregation, racist housing policies, and growth machine politics manifest themselves in nearly every community in this country. Whether through the decades-long campaigns to privatize school districts, the creation of inequitable funding formulas that saddle low-wealth communities with high operating and capital costs for their schools, or the long legacy of segregation, disinvestment in public education—perhaps more than any other sector—has contributed greatly to disparate education outcomes across race, class, and ability lines. Over time, these issues compound—with low-wealth schools struggling to maintain their buildings, to recruit and retain quality teachers, and to give students the resources and opportunities they need to succeed. These inequities occur both between and within school districts across the US.

A Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools addresses these long-term issues of health and environmental inequity, educational inequity, economic inequity, and structural racism by offering equitable goals, priorities, and $1.4 trillion in funding for our K–12 schools through federal Climate Capital Facilities Grants, Resource Block Grants, and expansion in Title I funding over the next decade. Without it, we risk deepening these existing inequities between facilities conditions, per pupil spending, and teacher retention rates, that contribute to poor health, educational, and economic outcomes for majority BIPOC school districts and communities.

A Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools aligns with the Biden administration’s goals of rescuing schools from the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic while creating jobs, addressing decades of disinvestment in the physical capital and educational resources of school facilities, delivering racial equity, improving health outcomes, slashing carbon emissions, and improving school resilience to extreme weather, all at the same time. It would also help the Biden administration achieve its Justice40 Initiative goal of ensuring that 40 percent of the benefits of its climate funding flows to disadvantaged communities. The massive public investments called for here would yield economic, educational, and climate benefits for decades to come.

To achieve a Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools, we propose $1.4 trillion in new funding over 10 years that would direct:

- $446 billion over 10 years for Climate Capital Facilities Grants to fund healthy, green, climate-friendly retrofits for every public school in the country. These grants would be paired with an additional $223 billion in low-interest loans to deliver healthy, green retrofits to all K–12 public schools. Grant funding would be targeted to school districts in the lowest-income areas, which will be prioritized for first access to funds in the program’s first three years. These retrofits will also include short-term measures to help schools reopen safely as we exit the pandemic. An additional $40 billion will be made available, over 10 years, for school resiliency measures, to fund additional green upgrades to schools to keep them safe in extreme weather and contribute to community resiliency. Today, over 50 million students attend public K-12 public schools—a number that will only grow. This bill would help them all.

- $250 billion over 10 years for Resource Block Grants to fund expanded staff, social services, training, and professional development in public schools with the greatest need; this would include $100 million in Educational Equity Planning Grants to pilot a process of eliminating intra-region education inequities in school funding.

- $69.5 billion annually in expanded Title I and IDEA Annual Funding to sustain operational support for the Resource Block Grants.

The Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools is also a jobs program. Investments in healthy green retrofits will generate 935,000 jobs per year (of which 272,000 are construction and on-site maintenance jobs); and the resource block grants support 339,000 educator resource jobs each year. Overall, this bill will fund 1.3 million jobs annually.

The country’s 105,000 K–12 schools currently emit 78 million metric tons of CO2 each year;9 they use 8 percent of all the energy used by US buildings. Decarbonizing the country’s K–12 schools would entirely eliminate that carbon pollution, the equivalent of taking 17 million cars off the road. School energy use can be fully decarbonized by performing deep-energy retrofits for school buildings, adding solar panels to school facilities, and switching to zero-carbon energy sources for any remaining electricity needs. And electrification will have local health benefits, by eliminating toxic fumes from in-building combustion of gas, oil, and/or propane. To date, schools have been constrained in making truly healthy, deep-energy retrofits because of high upfront costs. We propose using federal investment to cover schools’ full retrofit cost. For schools in the lowest income third of census tracts, we propose full grant funding for retrofits. Better-funded schools would receive a mix of federal grants and federal loans. Overall, this massive federal investment in schools will drive down the cost of deep energy retrofits for the entire building sector, by creating and growing businesses, building workers’ capabilities, and lowering costs for technologies and materials. This would help advance racial justice while healing the planet—and schools’ balance sheets.

We estimate that retrofitting all the country’s K–12 public schools would cost $669 billion. This would also cover community green infrastructure improvements like school-site solar and battery, as well as community involvement throughout the retrofit process. We recommend that the federal government cover two thirds of this upfront cost—$446 billion—through Climate Capital Facilities Grants, with the final third coming from low- and no-interest loans from the Department of Energy or Department of Education, as these retrofits should cut most annual utility bills by over 50 percent. Schools in the most vulnerable third of census tracts should have their retrofits entirely funded by grants, and would be prioritized for funding in the program’s first three years. Overall, to comply with President Biden’s executive orders on environmental justice,12 we recommend that retrofits for schools in the most vulnerable third of census tracts be entirely grant-funded, that schools in the middle third have two thirds of retrofit costs covered by grants, and that schools in the richest third of census tracts have one third of their retrofit cost covered by grants. We use the CDC’s Social Vulnerability index to measure vulnerability.

Healthy, green retrofits to all the country’s K–12 public schools would create 935,000 jobs per year across the economy. Of those, we estimate that 272,000 jobs would be on-site construction and maintenance jobs compensated at union rates. Our estimate of projected place-based spending, based on our proposal’s equity criteria, finds that on-site jobs would be evenly distributed between red states and blue states (based on 2020 electoral college vote), with 137,000 going to blue states and 132,000 to red states, plus 3,000 to Puerto Rico.

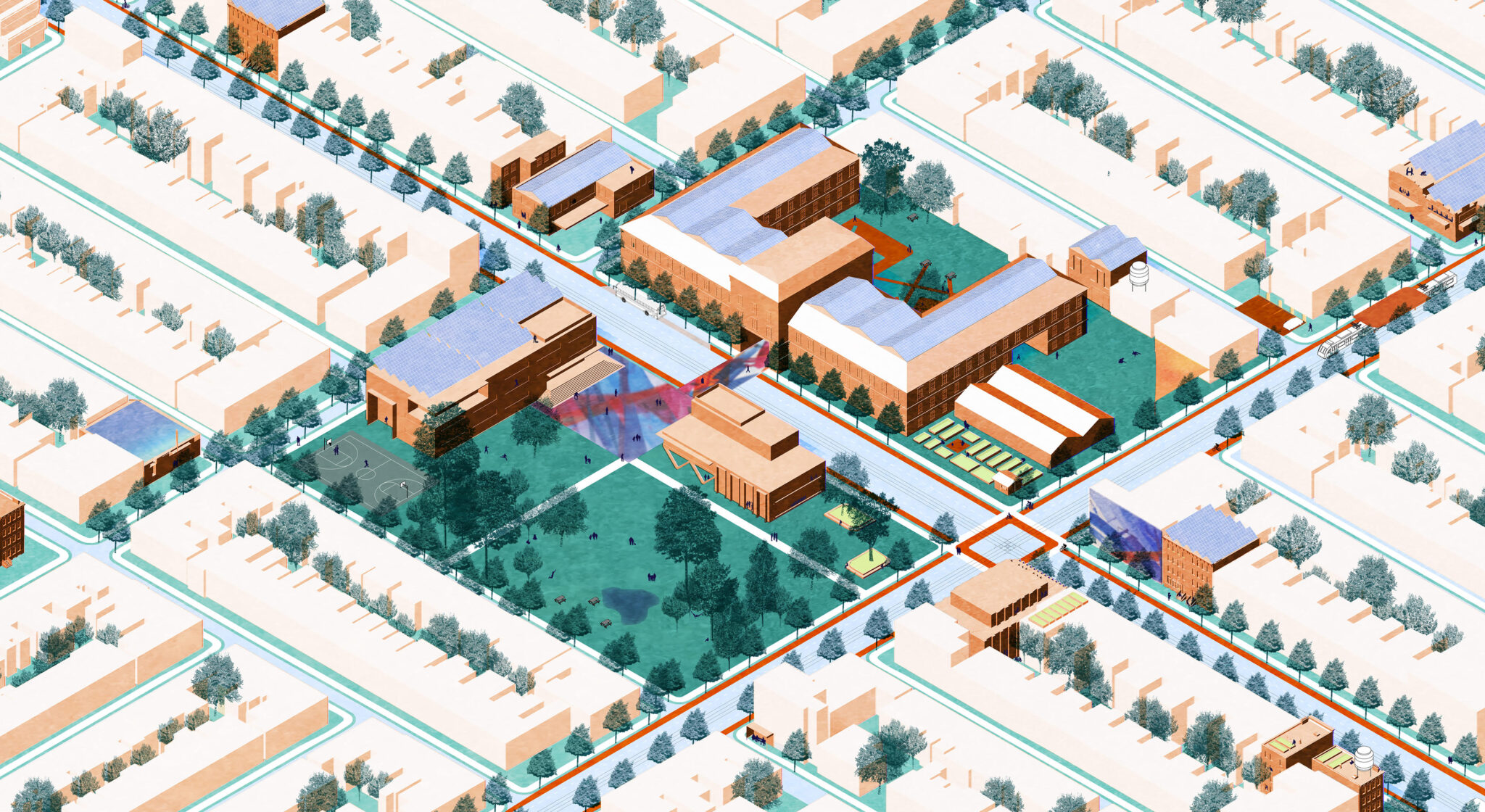

These retrofits will turn schools into neighborhood resiliency hubs, making them a key node of overall green community infrastructure. With these retrofits complete, schools that can generate and store their own energy, and that contain large meeting spaces from auditoriums to gyms, could better serve as key disaster relief centers during extreme weather events. Retrofits would benefit from technical support from the Department of Energy and its national labs, like the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Moreover, the retrofits will create ideal learning laboratories to promote deep engagement with STEAM learning and skills. Using the school as a learning laboratory, children and educators will be able to leverage the new facilities to develop project-based learning activities and programs that are rooted in land-based scientific discovery and engagement. Through providing early and repetitive exposure to real-world scientific and engineering learning, these schools will generate a pipeline of students who have the skills and knowledge to pursue STEAM careers and will contribute to a labor force that better reflects our nation’s diversity.

The Resource Block Grants will establish well-resourced classrooms and school facilities across the country while creating 339,000 new, good-paying jobs in schools. In schools with the greatest needs and that serve low-wealth students, these block grants can be used to support hiring more educators, lowering teacher-student ratios to 1:12 for K–8 schools and 1:15 for grade 9–12 schools. We will reach these ratios by hiring additional classroom teachers (a head and associate teacher for all K–grade 3 classrooms) as well as learning specialists, including math and reading specialists and afterschool staff, for all K–grade 12 classrooms. Research suggests that higher salaries and greater resources in classrooms and schools are vital to teacher retention and improving student educational outcomes.15 These grants can also be used to build up and diversify the pipeline of educators and paraprofessionals trained in trauma-informed teaching and learning practices. The expansion of the educator pipeline, along with resourcing development and operations to retain and attract existing educators to our nation’s most under-resourced schools, will address the forecasted educator shortages of the next decade. States and local districts may also use these funds to retain and promote these federally funded and professionally trained educators to address the expected rise in educator retirements in the coming years.

Although funding and administration of public schools are highly localized, governance and local control are not entirely democratic, representative, or transparent. Nearly 95 percent of school boards have elected members, but a growing number of these local elections receive donations from national coalitions of educational reformers that can disenfranchise less monied local interests. Moreover, many urban school districts lost their democratically elected school board when their state governments took over the fiscal management of these districts and dissolved their locally elected boards.

Educational Equity Planning Grants will help to address one of the most critical issues of educational sustainability: inequities in school funding formulas that limit district budgets to the values of the property taxes in their jurisdictions. The Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools builds on the work of fair housing and educational equity advocates with the introduction of Educational Equity Planning Grants to encourage the formation of regional school planning and funding mechanisms to minimize intra- and inter district disparities. These grants build on the FY 2021–22 appropriation proposal from the Biden administration and the Department of Education for Title I Equity Grants, which seek to address funding inequities in Title I allocations, by addressing inequities found in state and local allocations to school districts and individual schools. The problems facing schools are not simply a lack of resources, but the inability to develop sustainable infrastructure, including staffing facilities, administration, and funding of public schools. As part of this initiative, we are proposing a series of transformative pilots, such as the educational equity planning grants, by establishing regional councils of school districts composed of educational stakeholders like local and state officials, state and local educational departments, students, staff, educators, administrators, school planners, and financial officers.

Research demonstrates that barriers to improving school facilities in particular are the result of both lack of funding and lack of expertise.21 Eligible districts will be offered planning grants to allow them to:

- Document past educational inequities in the region,

- Identify or create funding sources for a regional pool to finance school districts, and

- Create a multi-year plan that lays out district and regional-specific benchmarks to achieve greater equity between school budgets in the region.

Expanded Elementary and Secondary School Act (ESEA Title I) and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) funding addresses years of little to no relative growth in these spending categories. Both Title I and IDEA funding are intended to funnel resources directly to the students and schools who need them most. However, in reality, most schools and administrators must apply these funds in ways that are meant to replace funding decreases from federal, state, and local budgets. So, rather than increasing resources for high-need students and schools, these funds have become stopgaps in cities and states where austerity-minded officials attempt to defund public education. Title I and IDEA funding increases are often impactful in their first year, and then slowly lose efficacy over time as other funding sources are decreased in proportion to the new increases.

In Philadelphia’s highest-need schools, for example, this means that principals are forced to use Title I funds to staff positions that are not centrally allocated as a result of unreliable local, state, and federal funding streams. When needed infusions of federal funds from the 2008 foreclosure crisis (where state and local revenues decreased from falling property values) ended, high-need schools lost their reading specialists, assistant teachers, and other vital staff positions. Local principals must use these discretionary funds to address multiple needs—far more than existing funds can adequately address. By increasing these discretionary funds and providing new sources of federal funding to address systemic disinvestment, a Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools will remove these tradeoffs for under-resourced administrators. It will also invest a portion of these funds to hire more staff in state-level education departments and local educational agencies, increasing state and local capacity to better direct resources to schools that need it for increased equity.

In sum, the Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools addresses key resource gaps so that our most disinvested public schools can act as engines for health, environmental, educational, and economic equity. Instead of federal policies that encourage schools to Race to the Top after decades of deferred maintenance, high debt service payments, targeted disinvestment, and decreasing staff-to-student ratios, let’s invest in the public schools that need it the most by affirming their local rights and control: to create green and healthy buildings in neighborhoods, using labor from the community, to improve educational outcomes and make school facilities safe and resilient spaces for all. A Green New Deal for K–12 Schools invests in building up the pipeline of green workers, innovative educators, engaged youth, and community-centered school facilities.

Meet the authors

Akira Drake Rodriguez

City and Regional Planning,

University of Pennsylvania

Daniel Aldana Cohen

Assistant Professor of Sociology, UC Berkeley,

Director of the Socio-Spatial Climate Collaborative, UC Berkeley

Kira McDonald

Xan Lillehei

Al-Jalil Gault

Gensler

Nick Graetz

University of Minnesota

Billy Fleming

Wilks Family Director,

Ian L. McHarg Center, University of Pennsylvania