The Effects of Lithium Mining

Although lithium is geologically abundant, the vast majority of lithium extraction is concentrated in Australia, Chile, Argentina, and China. At the same time, the lithium extraction frontier is shifting to new regions as downstream battery and EV producers scramble to meet increasing demand, and governments, especially in China, the United States, Europe, and Canada, incentivize domestic extraction, expand domestic supply chains, and promote geopolitical alliances that facilitate trade in lithium and other “critical minerals.” The result is intensified extraction within the countries that currently lead production, alongside prospecting and exploration in locales with previously small or non-existent lithium sectors.

Lithium can be found in a wide range of deposit types: rock, including both hard (pegmatite, most commonly spodumene) and soft (clay), and brine (including both continental salt flats and geothermal). In addition, lithium can be recovered from the “produced water” that is a byproduct of oil and gas production. All current operational lithium mines are either brine or hard rock; the rest of these deposit types (clay, geothermal, and oilfield) involve extraction techniques that have only been tested at the pilot scale. Thus, lithium extraction and processing projects can vary a great deal, and, with new extraction techniques, there remains considerable scientific uncertainty regarding the environmental consequences of commercial-scale production, including over water use and waste streams.

Like all forms of mining, lithium extraction and processing comes with a number of concerning social and ecological impacts. These include pollution, water depletion, loss of biodiversity, threats to human rights, nonmining livelihoods, and Indigenous sovereignty and cultural integrity.

The threats to human rights and Indigenous sovereignty are especially pertinent given that much existing and proposed lithium mining is on or near Indigenous lands. In the United States specifically, 79 percent of known lithium deposits sit within 35 miles of Native American reservations. Lithium mines on Indigenous lands have often been developed without substantive enforcement of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which is based on an international human right standard, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, that allows Indigenous people the right to give or withhold permission for the advancement of projects that would affect them or their land, or substantive community participation. While many harms of mining may be mitigated, the destruction of sacred or tribal lands transforms landscapes permanently. The lack of substantive enforcement of FPIC and respect for Indigenous sovereignty is further discussed in the global case studies of mining sites below.

In this report, to illustrate the oftentimes devastating consequences of lithium mining, we focus on a subset of deposit types and geographies encompassing both ongoing and proposed lithium extraction. While not an exhaustive analysis of all projects and their impacts, our selection captures the range of current and potential harm.

United States

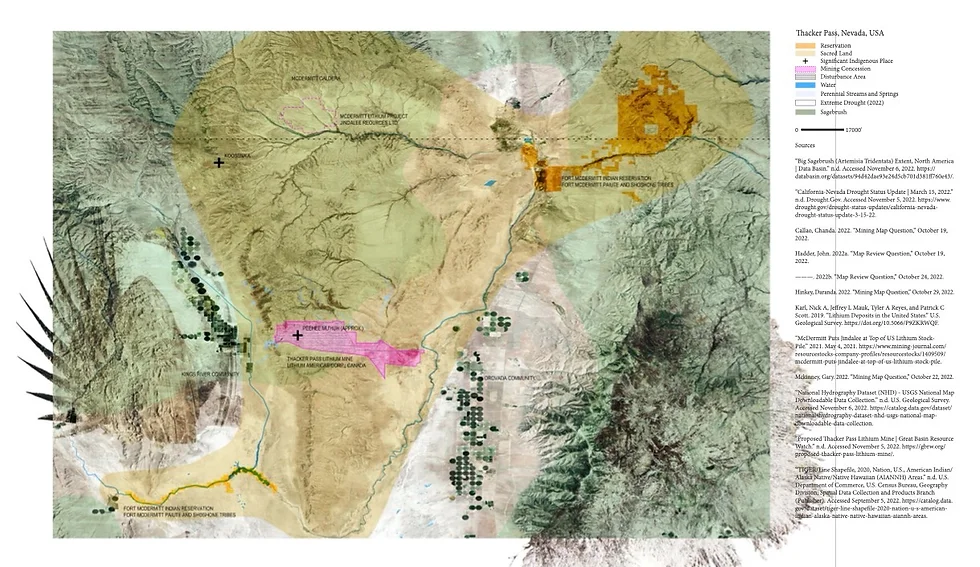

Mining regulation in the United States is overall deficient and seriously outdated. On federal public lands, mining is still primarily governed by the General Mining Act of 1872, which contains no water or environmental safeguards nor provisions for Indigenous consultation, let alone consent. At present, only one small lithium mine operates in the US: Silver Peak, a brine deposit located in southwest Nevada and run by the Albemarle Corporation that currently produces just under 1,000 metric tons of lithium per year. However, the drive to onshore US lithium mining points to a significant increase in rock extraction. Near the end of the Trump administration in early 2021, the US Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) approved a massive new lithium project on leased federal lands a few hundred miles away in northwestern Nevada’s Humboldt County called Thacker Pass. Thacker Pass is the site of a large soft clay lithium deposit. Lithium Nevada, the corporation developing the project and a subsidiary of Lithium Americas, claims that it can produce 30,000 metric tons of lithium per year, which if it were a country would make the Thacker Pass project the second largest producer of lithium in the world.

The proposed mining at Thacker Pass would disturb approximately 5,695 acres and last for 41 years, and at the end of its operating span the open pit mine would be entirely filled in. Once up and running, the mining operation would use approximately 5,200 acre-feet of water per year (equivalent to the water usage of around 15,000 US households) from a nearby groundwater well. It would also produce 354 million cubic yards of clay tailings waste over its lifespan using novel technology, which has the potential to leak and contaminate area soil and water.

This project has faced significant local resistance from various groups, including environmentalists, ranchers, and Indigenous tribes, because of a lack of consultation with local tribes and an inadequate environmental review. The definite or potential ecological impacts of Thacker Pass include groundwater depletion, pollution, and habitat destruction for species like sage grouse, golden eagles, Lahontan cutthroat trout, and pronghorn antelopes. Ranchers in particular are concerned that the mine’s water usage will negatively impact their cattle grazing operations. Additionally, Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) is a group of Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe members organizing against this project proposed for the land they call Peehee Mu’huh (rotten moon). This area has cultural and spiritual significance to tribal members because they harvest traditional foods and medicinal plants in the area. Peehee Mu’huh is also the site of multiple massacres of Indigenous people by US soldiers, including the killing of dozens of Paiute people in 1865. The exact locations of victims’ graves remain unknown; documents that are available do not specify them. The last Indian massacre recorded in the area occurred in February 1911, near the Santa Rosa mountains. Unlike some other forms of harm, cultural harms like desecrating sacred land have no possibility for mitigation.

A coalition of ranchers (Edward Bartell), Indigenous groups (the People of Red Mountain, the Burns Paiute Tribe, and the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony), environmental justice organizations (Great Basin Resource Watch), and environmental groups (Basin and Range Watch, and Wildlands Defense) sued the BLM, seeking to stop the Thacker Pass mine. In February 2023, the initial ruling rejected most of the mine opponents’ arguments but did rule that BLM broke the law in permitting the project on claims land that were not validated as required by US mining law. The judge, however, did not vacate the permit, as was seen in two other cases, allowing for construction to continue. On February 21, 2023, an emergency injunction was filed after the ruling to protect the affected land, biodiversity, and cultural sites, but the request was rejected. In March 2023, the Ninth Circuit court ruled to allow initial construction to begin, pending review of the environmental justice and conservation groups’ appeal. Efforts to appeal the March 2023 court ruling and stop the Thacker Pass project have continued.

Portugal

Portugal has the largest lithium reserves in Europe. However, at 60,000 metric tons, it is still relatively small when compared to the reserves of major producers like Australia and Chile. In 2021, Portugal was producing low-grade lithium for glass and ceramics usage, which accounted for just under 1 percent of global lithium production. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Portugal took on loans from the EU and the International Monetary Fund that came with structural adjustment policies to incentivize exploration for potential new lithium mining and processing; similarly, the European Battery Alliance and Raw Material Alliance has promoted extraction among EU member states, helping to coordinate supply chains and secure project funding. The EU wants to have a more self-reliant supply chain for the energy transition, and the Portuguese government has been approving new exploration for lithium.

British mining company Savannah Resources has proposed the Barroso lithium mine in northeastern Portugal, which would be the largest lithium mine in Europe. But this project has been delayed for years because of ongoing environmental reviews and community resistance. The Barroso mine would produce around 14 million metric tons of tailings over 12 years, which would be enclosed by waste rock. If the waste mound fails, the potentially toxic tailings waste could flow into nearby rivers. Many residents of Barroso live off the land, particularly through “agro-sylvo-pastoral”–smallholder agriculture; this project presents a direct threat to their environment and their livelihoods. Indeed, the Barroso region is designated a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Local Community of Common Land of Covas do Barroso has filed a lawsuit against Savannah Resources claiming that the parcel they purchased for the mine is on land that has long been held in common—land that cannot be sold and is managed jointly by community members.

Chile

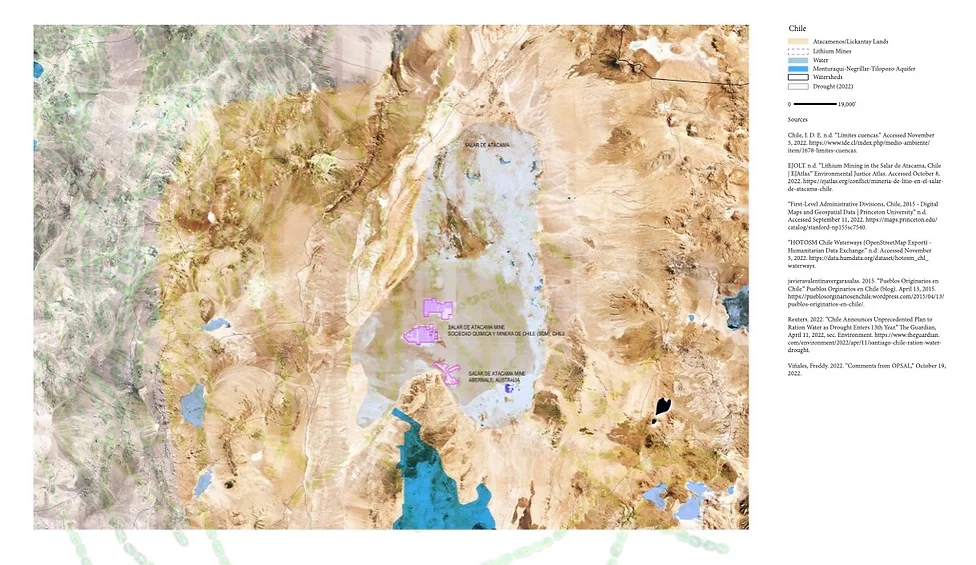

Chile is the second-largest producer of lithium in the world, trailing only Australia at 26,000 metric tons in 2021. In Chilean law, brine is treated as a mineral rather than water, and mining is regulated at the federal level. Lithium was declared a strategic resource and nonconcessionable in 1979, which has in effect limited the number of mining projects to those with concessions that predate this statutory change. Currently, two large-scale lithium mines are in production on the Atacama Salt Flat, operated by SQM and Albemarle. However, the country’s state-owned copper company, Codelco, plans to explore and exploit lithium in the Maricunga Salt Flat, as does Minera Salar Blanco, a joint Australian-Chilean-Canadian venture. In January 2022, a tender for new lithium contracts was suspended by Chile’s Supreme Court on the grounds that the auction did not specify specific territories and thus made prior consultation of Indigenous peoples impossible; however, the progressive Boric government has had plans to establish a state-owned company and enter into joint ventures with foreign lithium companies.

The Atacama Salt Flat is surrounded by Andean mountains and is located in the Atacama Desert, the oldest and driest desert in the world. Lithium extraction in Chile threatens the health and viability of Atacama ecosystems, which are important for local communities and humanity more broadly. Scientists recently identified plants in the Atacama that are adapted to the arid conditions and genetically similar to food crops, which means they may be highly useful for adapting agriculture to a warming planet.

The ecological impacts of brine extraction in Chile, particularly its water usage, have come under increasing scrutiny. Earlier this year, the Chilean government sued lithium mining company Albemarle (along with Antofagasta and BHP for their copper mines) because of their exploitation of the Monturaqui-Negrillar-Tilopozo aquifer and impact on surrounding ecosystems. The other major lithium mining company operating in Chile, Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (SQM), has been subject to numerous investigations and lawsuits for labor, financial, and environmental violations. For example, in 2016 Chilean regulators initiated sanctions against SQM for overconsuming freshwater and brine, and also for tampering with their own environmental monitoring systems. In January 2019, regulators accepted a company plan to bring its operations into compliance with its contract and Chilean law. But later that same year, the Council of Atacameño Peoples (Consejo de Pueblos Atacameños, or CPA)—which represents the 18 Indigenous Atacameño communities that live around the Atacama Salt Flat—successfully appealed the plan. Their appeal forced the company back to the drawing board, resulting in a new commitment to cut brine and water use in half—though it certainly remains to be seen whether the company will achieve these goals.

Argentina

Argentina is the fourth-largest producer of lithium in the world—6,200 metric tons in 2021—but it has around 50 proposed projects, which could dramatically increase its production and push it above Chile and China. As in Chile, lithium mining creates tensions within communities because of the trade-offs between economic and infrastructural benefits offered by corporations (that are lacking from the government) versus the social and ecological harms that mining causes, a contradiction that companies can exploit to their advantage. Brine extraction threatens nearby Indigenous pastoralism and the unique wetlands full of important biodiversity, including species like flamingos, “pumas, Andean foxes, vicuna [sic], hairy armadillos, and endangered Andean mountain cats and short-tailed chinchillas.”

Mining regulation is mostly decentralized in Argentina and varies significantly at the provincial level. This is the result of federal deregulation in response to structural adjustment in the early 1990s, which also provided corporations with incentives to mine; previously, natural resources were owned by the federal government. This “localized governance” does not correlate to addressing community concerns around lithium mining projects; a multinational mining company and a provincial government or an Indigenous community are often on unequal footing in terms of negotiations.

As a signatory of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Argentinean government is ostensibly supposed to obtain Free, Prior and Informed Consent from Indigenous peoples for lithium extraction that affects their lands. However, as in other countries, community members near lithium mining in Argentina have noted a lack of information from both companies and governments on the potential risks and negative environmental impacts of these projects. Resistance to lithium extraction projects varies significantly between and within provinces, as a result of factors like power and resources of local Indigenous movements, proximity to population centers, and provincial government policies for mining.